There are regions where communities no longer believe in the National Program for the Integral Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS) and they regret, despite themselves, having believed in the Peace Agreement signed five years ago between the Colombian State and the former FARC guerrillas. While recognizing some of the benefits of this initiative, they also complain about its non-compliance.

After the issuance of Decree 896 of 2017 that created the PNIS with the objective of attacking the drug problem, several leaders and social organizations agreed that the Program was an invaluable opportunity to cut the link of thousands of families with illicit crops, but every day that passes and what was expected is not met, the communities lose confidence in the State.

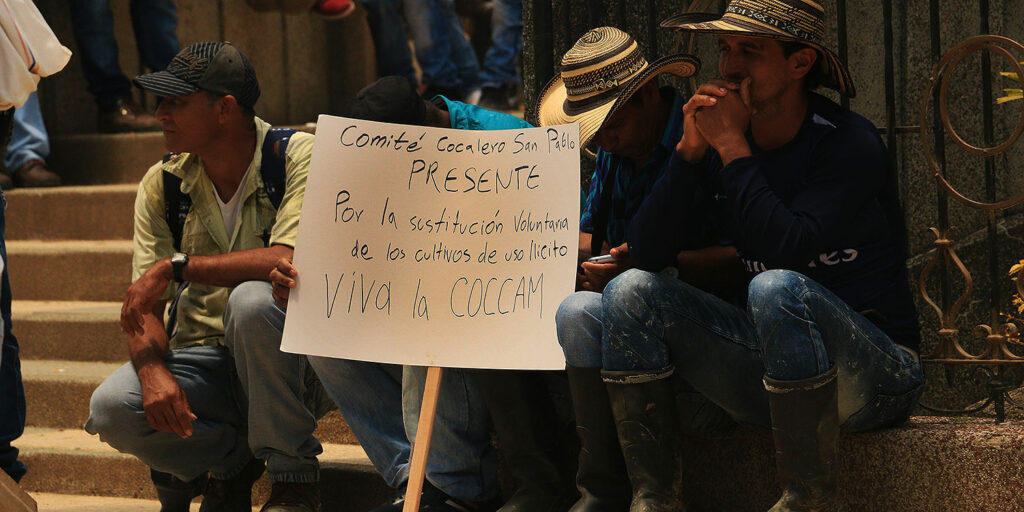

One of those visible faces complaining from the regions is Arnobis Zapata, national spokesman for the National Coordination of Coca, Poppy and Marijuana Growers (Coccam), who early on became a standard bearer for the implementation of the Peace Agreement, especially the PNIS.

“This government (of Iván Duque) from the beginning stated it did not agree with voluntary crop substitution and expressed that it was not going to be one of its main policies in the fight against coca crops and, for that reason, it has not allocated the necessary budgets for the PNIS. This government has no political will,” says this leader from southern Córdoba.

The history of the substitution of illicit crops in Colombia comes from programs such as the National Alternative Development Plan and Forest Warden Families, in which economic transfers were not direct, but through some goods and services, and which sought to comply with rural development policies: land titling, social housing and access to health services, drinking water, education, among others.

With the PNIS, as conceived in the Peace Agreement, a comprehensive project was proposed. “If one is asked ‘and how are you doing with what you are doing’, well, wonderful, perfect, everything divine. But that is not the reality. One has to be self-critical,” says Hernando Londoño, National Director of the PNIS, attached to the Territorial Renewal Agency (ART) and who has been in charge of the initiative for three years.

Since Havana, a model was planned that would benefit coca-growing, non-growing and coca leaf-gathering families, so that these villages would be free of illicit crops. At the time of its implementation, it was conceived as a population-based program with direct economic transfers to the families. There, the PNIS contemplated payments of 36 million pesos for each family registered as part of the Immediate Family Attention Plan.

The payments would be delivered through five components: immediate food assistance payments, for 12 million; technical assistance support, for 3.2 million; delivery of inputs and materials for food security projects and home gardens, for 1.8 million; short-cycle productive projects, for 9 million; and long-cycle projects, for 19 million.

Obviously, the program was born without thinking that it was going to enroll almost 100,000 families,” says Londoño. So, 100 thousand families for 36 million pesos are already worth 3.6 billion pesos and the State does not have that money. So, we start with a debt of 3.6 trillion pesos to be executed in two years”.

The official insists that the PNIS was poorly planned in aspects such as the timing of technical assistance: “How long does it take the State, which is very slow in itself, to get the money to hire, to start operating, to hire an operator and that operator to hire technicians and go out to provide technical assistance? That does not take 24 months, because the assistance alone was thought to be invested in 24 months”.

With all these remnants, the PNIS began and the families were leaving, as never before, the coca leaf. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states that, as of December 2020, 43,711 hectares of illicit crops had been eradicated voluntarily and with assistance in the 14 regions and 56 municipalities where the Program is being implemented.

As of December 2020, 99,097 families had registered to obtain the benefits of the PNIS, of which 67,251 are listed as growers; 14,989 as non-growers; and 16,857 as harvesters. However, according to information from the Directorate for the Substitution of Illicit Crops as of March 31, 2021, of the total number of families involved, 80 percent were active; 10 percent had withdrawn; 6 percent were entering; and the remaining 4 percent were in a state of suspension.

Regarding suspensions, the data show that these were mainly due to non-compliance with the required program activities (1,044), non-compliance with the requirements of the beneficiary families (645) and non-compliance with administrative requirements (454).

Regarding exclusions, 2,181 of the cases correspond to the low density of illicit use crops in the postulated lots -one of the PNIS targeting criteria-; 1,730 are due to the fact that they were not accredited by the Community Assemblies or that the Community Action Boards do not recognize them; 1. 269 for not complying with the obligation to participate in the required activities -such as the monitoring and verification exercises of the eradication of illicit crops, the activities of the technical assistance operators and the implementation of productive initiatives-; 1,007 attended by other previous substitution programs; and 1,007 voluntary withdrawals.

In the Third Report to Congress on the State of Progress of the Implementation of the Peace Agreement, published in August of this year by the Attorney General’s Office, the control entity is clear in reproaching that there is no regulation to define the permanence of PNIS families in the Program.

Of the total number of registered families, by the end of 2020, 58,940 received the full amount of immediate food assistance, which corresponds to monthly cash amounts of one million pesos to be paid in 12 months for economic support. According to the Attorney General’s Office, that number rose to 68,950 by March 2021, thus, in three months this phase of the PNIS increased by 10 percent.

They question implementation

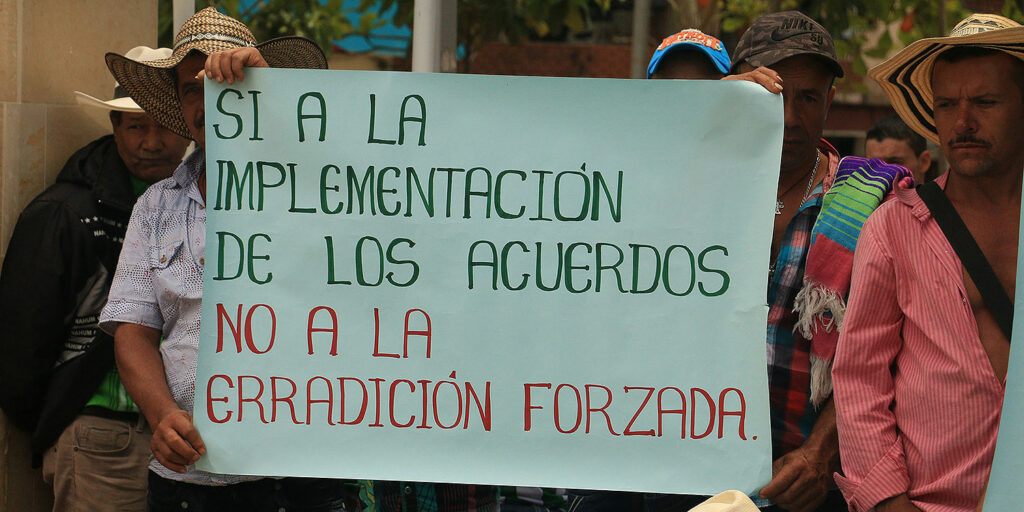

The non-compliances in the implementation of the Program and the onslaught of the Public Forces against peasants who cultivate coca leaf generated last May the protest of hundreds of peasants, who left their regions to join the National Strike called by trade union centers and student organizations and to plant themselves in key sites of Villavicencio and Buenavista, in Meta, or Altamira, in Caquetá, and demand, as one of the first points, the fulfillment of the PNIS.

Eucario Bermúdez, social leader of the municipality of Cartagena del Chairá, in Caquetá, says that his disagreement with the national government is because in the villages where he works, most families have received between three and four payments for food security, more than three years after the Program began.

In this municipality, there are a total of 2,347 beneficiary families and as of December 31, 2020, the total payments of the Immediate Attention Plans had been made to 1,342 families, according to UNODC. After that contribution, Bermúdez recalls, “they gave some seeds, some nets, some wheelbarrows, some zinc sheets, some hens. And the productive projects… nothing. That is no longer coming”.

Similar situations are experienced by farmers in the villages of Caño Amarillo, Caño Limón and La reforma, in the municipality of Vista Hermosa, Meta, where 2,202 families are enrolled in the PNIS. The communities emphasized that the initial amount of food assistance, 12 million pesos, was paid in full. Then “a project for a vegetable garden with coriander seeds or something like that came along… and that was it,” acknowledged a farmer from the region who asked his name to be withheld.

Several leaders agreed that the current national government has discarded the PNIS implementation route that had been proposed with the communities during the administration of President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) and proposed another one without socializing it.

“President Duque wants to fulfill the 100 thousand families, he wants to deliver the resources to fulfill the 100 thousand families, even if they are 3 trillion pesos. We have already invested more than 1.7 trillion, then what is left is 1.8 and I have 700 billion this year, that is, I will be left with 2.5 trillion pesos at the end of 2021”, highlights the PNIS director.

However, given the failure to meet the deadlines, “what has happened is that the people have eaten what the government has given them,” Zapata says. The government is handing over the resources to the peasants on a drop-by-drop basis, every two years a new component comes in, and it is only from the Immediate Attention Plan”.

When Farid Murcia, leader of Bajo Caguán, is asked about the fulfillment of the productive projects in the region, after laughing with disdain, he says “nothing, nothing at all”. He agrees that the actions have been focused on the Immediate Attention Program (PAI), in several regions still unfinished, and the rest of the components have been unfulfilled.

“Progress in the delivery of resources for short-cycle and long-cycle projects is still far below the established goals,” states the Attorney General’s Office in its report. It also reminds that in the cases where some of these phases have been advanced, it should be concerned about accompanying the families in a more assertive way so that, as the Coccam spokesman says, the resources of the Program are not lost.

“As this control entity has learned, the technical assistance consists of characterization visits, definition of investment plans and delivery of inputs, but they do not continue once the process is completed. Although the DSCI (Directorate for the Substitution of Illicit Crops) has a territorial support team, this is not enough to cover this process of constant technical assistance for the families in the Program”, states the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Another point that shows timid progress is the community PAI, which had been formulated as actions to improve the conditions of each of the villages that joined the PNIS.

The communities denounce that there is no major progress in the construction of health posts, rural day care centers, school meals, small infrastructure works and employability. In its report, the Ombudsman’s Office also found debts in some of these areas.

With respect to the Municipal and Community Integral Plans for Substitution and Alternative Development (PISDA), which proposed to implement programs in the territories related to the social organization of rural property and land use, infrastructure and land adaptation, health, education and housing, among others, the Ombudsman’s Office shows progress.

As of March 2021, “there was a universe (sic) of 812 PATR (Action Plan for Regional Transformation) initiatives with PISDA marking, for 48 municipalities where PDET and PNIS coincide. Of these initiatives, 268 had an implementation route activated, and 353 were contained in the ART 2020-2021 work plans. These initiatives are concentrated in the municipalities of Tumaco (27), Puerto Asís (23), Puerto Rico (20), Miranda (19), La Montañita (16), Puerto Leguízamo (10), Mesetas (10) and Orito (10)”.

Collectors, bearing the brunt

The harvesters, also known as ‘raspachines‘, who once served as laborers to scrape the coca leaf, have been the ones who have been most neglected. This is what peasant spokespersons and the Attorney General’s Office agree on.

For one year of work in tasks of community interest (such as school canteens or rural roads) they would be paid 12 million pesos. According to the last PNIS monitoring report delivered by UNODC, as of December 31, 2020, 5,701 collectors were involved in community interest activities in which they performed maintenance on 15,305 kilometers of tertiary roads or bridle paths and 9,682 public spaces.

In some regions they were paid for this work; others have not even received their first payment, according to complaints from communities in some villages in the municipality of Mesetas, Meta.

“Although this component presented an improvement with respect to 2020, it continues to be the one with the greatest lags in its implementation, since administrative and budgetary efforts are concentrated on complying with the family PAI of the bulk of the families assigned as growers and non-growers,” reads the report of the Attorney General’s Office in relation to the situation of the harvesters.

In the municipalities of Puerto Libertador, Montelíbano and San José de Uré, in the south of Córdoba, the collectors received payments for the first phase, but in the municipality of Tierralta not even one of the 132 collector families has received the first payment, and the response the communities say they have received from the national government is that “there are no resources”.

Several communities in Mesetas, Meta, where 1,103 families were enrolled in the PNIS: 712 growers and non-growers and 391 harvesters, agree with this version. Many of the latter got tired of waiting for the Program’s promises and went to the regions of Cauca, Northern Santander or Guaviare to continue working with illicit crops.

“There are those collectors that every time we hold meetings, they complain to us (the leaders who promoted the Peace Accord), because at the end of the day we were crucified for playing the role of redeemers. We were the ones who took the government there,” laments Zapata.

No clear solutions

The PNIS proposed to technically assist productive projects to which the families were accustomed with a 19 million pesos budget to generate income in the lands they inhabited. However, in environmentally protected areas the reality is different.

In the case of the National Natural Park System, restrictions on anthropogenic activities are quite strict. According to information provided by National Natural Parks, in the protected areas administered by this entity in Meta, Guaviare and Caquetá there are 1,855 families with 5,569 people as characterized between 2015 to 2021 that should be engaged in conservation or ecotourism activities, but in practice they have based their economies on cattle ranching and coca leaf cultivation.

“If coca leaf cultivation must end, well, it must end, but where is the solution? If today a plate of food is on the table it is because coca leaf is producing it, so ‘I take this away from you, but I will give you the plate of food with this’, but that has never happened, it is only ‘pass me that plate of food and you will see how you defend yourself'”, comments Ronald Echeverri, president of Nueva Colombia, one of the villages of Vista Hermosa, in Meta, which is part of the Serranía de La Macarena National Natural Park.

The communities settled in areas of environmental interest aspire to “territorial security”, that is, they want to be granted land titles for the lands they inhabit. Some settlers have been settled in this region since the 1960s, long before it was declared an unadjudicated zone.

Londoño recognizes that when the PNIS has come to the territories to try to implement the productive project, the people have no land: “Today we find all the problems. People are asking for land and a substitution program cannot become a land program, because that is what the National Land Agency is for”.

I know that people who have titled land do not plant coca,” he continues, “because they know they will lose it. So, the people who plant illicit crops are either in the non-titled Law 2 reserve zone or they go into the parks or into the indigenous reserves or the community councils or wherever they don’t lose anything because they know that if they are caught, they will lose the land.

To solve the problem of the communities settled in the Forest Reserve Zone, the national government has formulated proposals such as the Natural Conservation Contracts, which grant the families settled in these areas the right of use for up to 10 years, extendable from 1 to 10 more years, in activities that the land management plans allow, with payments for environmental services of 800,000 pesos delivered every two months.

“It is expected that before the end of this government 9,596 Natural Conservation Contracts will be delivered in Colombia, a process that additionally has a key component to implement processes of voluntary substitution of illicit crops in Forest Reserve Zones”, published in February of this year the Presidential Council for Stabilization and Normalization.

However, several communities expressed their mistrust to this portal because they believe that after these contracts are terminated there would be no legal guarantee that would allow them to continue living on those lands they have inhabited for decades.

Pedro Arenas, a Viso Mutop researcher, recalls that with several families located in Parks they signed individual PNIS pacts, by which the State was obligated to provide maintenance money. “More than four years have passed and the government, with multiple excuses, has delayed the fulfillment of the commitments with the families,” he says.

Londoño has highlighted that one of the biggest obstacles is the lack of funding for the program, the poor planning with which it was formulated and the alleged reluctance of the National Natural Parks’ directors to develop productive activities in these protected areas.

Dr. Londoño,” says Arenas, “has always used the excuse of blaming everything that happens with the program on the previous government, on the previous officials. I am not going to defend either the previous president or the officials who were originally in charge of the program, what I want to make clear is that three years have passed and this government should have found a solution to the problems it found in the PNIS”.

In its report, the Ombudsman’s Office highlighted that no initiative to generate income from park areas was being implemented. “As reported by the DSCI (Directorate for the Substitution of Illicit Crops), and corroborated by identifying that there were no investments for short or long cycle projects in these regions. On the other hand, in Forest Reserve Zones, an average investment per beneficiary of 95,344 pesos per family was identified in the productive projects’ component, whose cap is of $19 million pesos.”

For Zapata it is a work of the PNIS with National Natural Parks: “They are throwing the ball to each other and then go out and say that they cannot do things because there are limitations, but those limitations have to be resolved by the government, they cannot throw the limitations to the farmers as if they were the guilty ones”.

Custom-made

In several regions, a parallel initiative to the PNIS is being heard, which is published as “Custom-Made”. “There is no public policy document that shows what this program is about,” reproaches Pedro Arenas. According to information from the Directorate for the Substitution of Illicit Crops of the Territorial Renewal Agency, this proposal was adopted by Resolution 27 of May 6, 2020, however, this portal could not find it available on the Internet.

In a document that VerdadAbierta.com consulted from the Presidential Council for Stabilization and Consolidation, it is specified that “Custom-Made” is a joint and participatory strategy that is presented as an alternative for those families that are not registered in the PNIS.

“It is assumed that with the launching of these other strategies there would be money for other proposals, but to comply with the PNIS, which is derived from the Peace Agreement, there is nothing, which shows a little bit of bad faith behind saying that for the PNIS there is no money, but for another program there is,” complains Arenas.

In the regions there is already confusion with the appearance of this program. Some believe that now the PNIS becomes “Custom-Made”, others that the PNIS will not continue and now they must look for a place in “Custom-Made. What Arenas highlights is that the socialization of this program has not been clear.

The leaders who have followed up on this proposal see it as a “parallelism to the PNIS” and point out that in order for the peasants to enter this program they must eradicate without receiving any type of aid, they must own land and there is no fixed amount for the execution of the projects. Because of this, for Zapata, this program does not offer the necessary guarantees to the peasants and does not build confidence in the territories in the face of the already undermined image of the State with the implementation of the PNIS.

“It is a substitution strategy that depends on the territorial entities having a budget for it. It is like putting one more burden on the territorial entities and taking resources from where there are none to implement a thing that is not going to get anywhere because they are not going to be able to comply with any of it. If they cannot comply with the PNIS, which was supposed to have funding…”, sentences the Coccam spokesman.

Does the PNIS have a future?

Several leaders highlighted the commitment of their communities to voluntary eradication and the establishment of coca leaf free zones, as in the case of the Gaviotas village or the Nasa indigenous reservation of Candilejas, in the municipality of Uribe, in southern Meta.

These communities now grow bananas, avocados, cacao and passion fruit, but none of this is working: the poor condition of the roads makes agriculture unprofitable. The farmers hoped that the works promised in the Peace Accord would be carried out in harmony with the implementation of the PNIS, but so far there has been no clear progress.

A human rights defender from the Cauca Regional Peace Space, who prefers to keep his name confidential due to the high levels of violence in that region, acknowledged that in several parts of that region coca leaf crops are growing at the same time that the communities’ distrust of the Territorial Renewal Agency is increasing.

On the other hand, communities that have inhabited regions that are part of the Forest Reserve Zones, established since 1959 with Law 2, and that had eradicated all coca leaf, have begun to open patches in the Amazon jungle, as told to this portal by peasants of Bajo Caguán.

The national spokesman of Coccam considers that the most regrettable panorama is observed in those regions where there are no strong organizational processes and where there is discontent, but where their demands are not raised. “There, the government has done whatever it wants and the people have been given whatever they want,” he says.

The communities have considered not receiving any more PNIS resources if the national government does not sit down with the communities to correct the direction of the program, secure the resources and make progress in the comprehensive rural reform, because they are concerned that if the implementation is done in dribs and drabs at the end it will be said from Bogota that it was fulfilled when the reality in the regions reveals that it was a failure.

With political will, allocation of resources and linking it to the integral rural reform, there is a great possibility that a large number of peasants will get out of illegitimacy, says the Coccam spokesperson.

For its part, the Attorney General’s Office considers that the greatest challenges for the PNIS management are in materializing its contents in terms of inter-institutional articulation, coverage of the issues of greatest need together with the Integral Rural Reform, and follow-up of the operators contracted for the implementation of the Program.

“People continue with the idea that the PNIS can work, that it has opportunities. What must come is a government that has the capacity to understand that peasants are not criminals, that they are subjects of rights and that it must allocate budget to get them out of the situation they are currently in”, concludes Zapata who, despite everything, risks saying that the Integral Program for the Substitution of Crops for Illicit Use continues to be a viable alternative.