“While in the country there was talk of peace and the implementation of agreements to achieve the non-repetition of the violence, in our territories soon returned the threats, selective murders and massacres,” laments Juan Manuel Camayo, coordinator of the Tejido de Defensa de la Vida, of the Asociación de Cabildos Indígenas del Cauca Norte (ACIN), in charge of monitoring the human rights violations suffered by the Nasa people.

Between late 2016 and early 2017, the FARC laid down their weapons in compliance with the Peace Agreement and it was expected that the State would take, in a comprehensive manner, the areas controlled for years by the former guerrillas, with development and security, to fill that power vacuum, avoid new cycles of violence and settle the historical debts suffered by the communities hardest hit by the armed conflict.

However, criminality was faster than institutionalism. Hence, the situation described by Camayo is not exclusive to his region: it was replicated in different departments of the country.

Armed groups that used to border with the former FARC, guerrillas who distanced themselves from the peace process and men who took up arms again after demobilization, won the race and became involved in new disputes over territorial control. Those who are paying the price are the peasant, black and indigenous communities, to whom the Peace Treaty made the promise of non-repetition of the violence, but five years later, it has still not been fulfilled.

This is how Michel Forst, then UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, explained it in his report on the situation in Colombia in 2019: “The demobilization of the FARC-EP did not entail the mobilization and comprehensive state presence in the areas previously under their control, which allowed the reorganization of power at the hands of illegal armed groups and criminal groups around illicit economies, in the face of the inaction and/or absence of the State.”

Communities in Nariño, Cauca, Chocó, Antioquia, Córdoba, Bolívar, Putumayo, Caquetá, Meta, Guaviare, Arauca and northern Santander were able to rest from the din produced by the detonation of rifles and explosives during the final stage of the peace negotiations that took place in Cuba and the first months of implementation of the pact that put an end to a war that lasted more than 50 years.

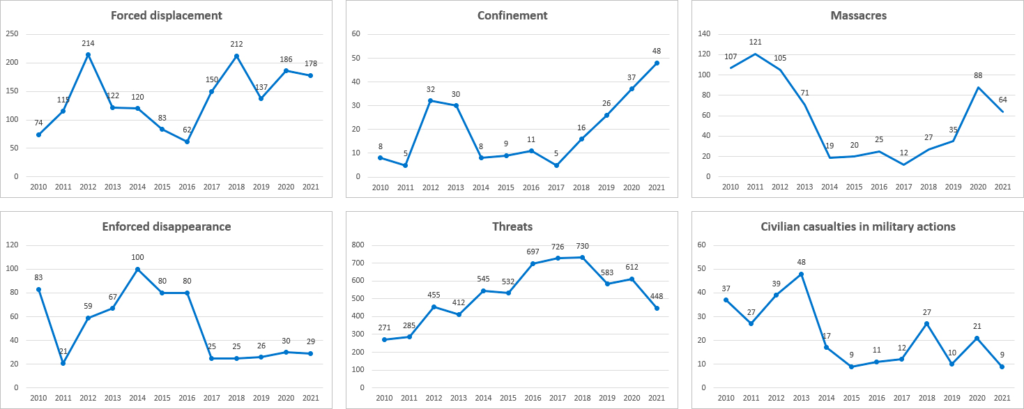

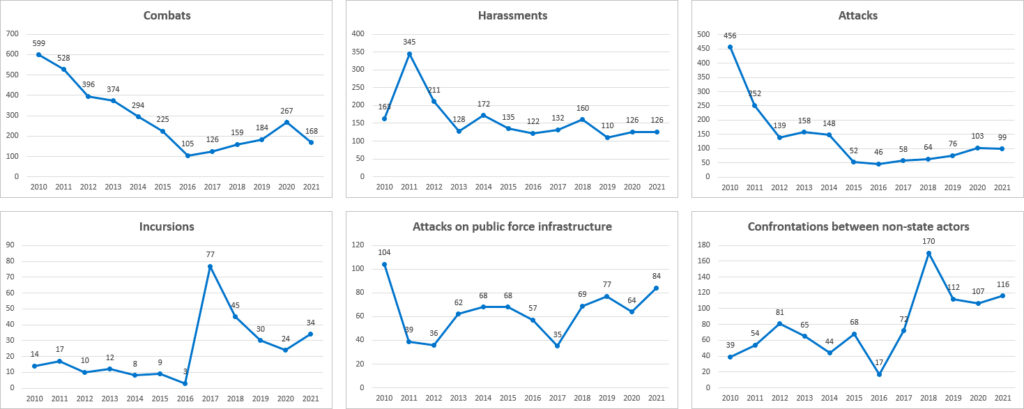

Between November 2012 and August 2016, delegates of then president Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) and the former FARC negotiated a six-point agenda to establish the Final Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace. During that time, forced displacements, confinements, massacres and civilian deaths due to clashes between armed groups decreased.

The only indicator that increased in that period were the threats and they are related to the dialogues: the meetings that victims of the conflict had with the negotiators in Havana awakened a wave of massive threats.

The paradoxical thing is that, starting in 2017, just when the implementation of the Peace Agreement and the policies of the so-called post-conflict began, the figures of violence grew again. This fluctuation is reflected in different indicators consolidated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The de-escalation and intensification of the conflict are also reflected in indicators over time. During the peace negotiations, confrontations between the security forces and the country’s largest armed group decreased, generating a positive effect. Once demobilized, they increased due to territorial disputes involving old and new armed groups. Most of the indicators and cases consolidated by OCHA, in the year 2017 register the turning point towards escalation of violence.

Regarding this panorama, Andrés Cajiao, researcher of the Area of Conflict Dynamics of the Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP), points out that, since the FARC laid down their weapons, the country has gone through three different stages.

The first one is the gestation of new armed groups. It happened on account of those leaders of the former FARC who distanced themselves from the peace process before the signing of the Agreement, as happened with Miguel Botache Santilla, alias ‘Gentil Duarte’, who operates in the regions of Meta and Guaviare.

The next stage is about territorial reconfiguration, that took place between 2018 and 2019, when “important resurgences are seen in different areas of the country, such as Nariño Pacific, Cauca, Catatumbo, the expansion of the ELN to the south of Chocó and the intentions of the Gaitanistas (AGC) to occupy Chocó from Urabá.”

The last stage takes place at the end of 2019, with the resolution of some disputes: “The ELN remains dominant in Catatumbo, although there is a dispute in Tibú; Arauca stabilized; in the south of Meta the Jorge Briceño Bloc remained under the command of ‘Gentil Duarte’ and ‘Iván Mordisco'”. However, Cajiao clarifies that intense confrontations persist in Nariño, Chocó, Cauca, Bolívar and Bajo Cauca Antioqueño.

New scenario

Following the demobilizations of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) and the FARC guerrillas, which occurred between 2003 and 2006, and 2016 and 2017, respectively, the dynamics of the armed conflict in Colombia changed substantially. It went from a conflict of large armed structures, with a strong vertical hierarchy and national scope, to several groups with local and regional scope.

“We have called the current situation focused conflicts or focused armed confrontations, to distinguish it from the previous decade, when there was a fairly generalized war situation. Now there is a change, which went through a period of de-escalation after 2012 and we entered into low-intensity conflicts,” explains Camilo González Posso, president of the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz).

This study center published last October 4th the report The Focus of Conflict in Colombia, in which it characterized the current armed groups and their actions. Among them are 22 structures of groups that emerged after the demobilization of the AUC and are known as narco-paramilitaries, 30 post-demobilization structures of the FARC and eight war fronts of the ELN guerrilla.

This investigation records that during 2020 the neo-paramilitary groups were active in 291 municipalities, the rearmed and dissident FARC in 123, and the ELN in 211. The investigation found eight focal points of confrontation.

In this regard, the report states that these "territorial focal points are not new conflict scenarios, but within them the dynamics were transformed by the armed reconfiguration and, with it, the levels of violence or the interconnections between them.

Gonzalez points out that the current situation is the result of the difficulties of the transition to the post-conflict: "With the signing of the Peace Agreement, structural problems of disputes over territory and power were not resolved through arms: it became part of a model to use arms to make wealth and retain power. These disputes are very strong and continue to have an impact over 300 municipalities in the country".

On the other hand, Kyle Johnson, researcher at the Conflict Responses Foundation (Core), states that the armed conflict has a smaller scope, is being degraded and criminalized: "It is going to be more and more local and regional. I don't think Colombia is going to have a conflict with actors who think about threatening the power of the central state and will stay at the local level”.

Regarding the degradation, he states that it is linked to the increase in the intensity of fights for territorial control: "Within these disputes there is a degradation in terms of the repertoire of violence against the civilian communities, which are harsher than those that existed before the peace negotiation with the FARC. That is why there is an increase in confinements and murders."

One of the main reasons Johnson attributes to this degradation is the youth and lack of training of those in charge of the illegal armed groups. "The main actors are younger than they were with the FARC and ELN 15 years ago. They are young people who grew up in a very different context, in another international moment and in another local culture. They don't have that root of peasant struggle," he says.

Camayo, from ACIN, agrees with this approach and maintains that the post-conflict has been much more serious than the armed conflict: "What the Peace Agreement did, was to divide armed structures and now we don't know with whom to talk about humanitarian issues. There is no way to have a dialogue and they do not respect the communities or their authorities”.

Unfortunately, the facts support this statement, since in northern Cauca, the decision of the indigenous reserves to exercise their right to territorial autonomy and self-government, after the demobilization of the former FARC, has cost the lives of dozens of members of the Indigenous Guard and ancestral authorities, as they opposed the presence of armed groups and the exploitation of illegal income.

Six FARC dissidents are present in Cauca, which broke away from the 6th and 30th fronts: the Jaime Martinez Column, the Dagoberto Ramos Column, the Carlos Patiño Front, the Rafael Aguilera Front, the Ismael Ruiz Front and the Diomer Cortes Front. In addition, there is the ELN and threats are constantly circulating in the name of the 'Aguilas Negras' and the AGC, although the police alleges that there is no presence of paramilitary groups in the region.

The effects of the post-conflict reconfiguration or disorganization of armed groups are also being felt in Catatumbo. Wilfredo Cañizares, director of the Progress Foundation, which monitors human rights violations in the border region of North of Santander, points out that before 2016 the control of each armed group was differentiated.

"After the agreements, there are today three groups of dissidents in the region: the 33rd Front, which the government says works with 'Gentil Duarte'; the Second Marquetalia, of 'Ivan Marquez'; and the 41st Front, of 'Otoniel'. From having the 33rd Front clearly established with its domain and interests, we went from having three dissident FARC groups in the region. There are tensions between the 33rd and the 41st, but fortunately the confrontation between the EPL and the ELN has decreased”.

Five years after the signing of the Peace Accord, the communities that have suffered the most from the war feel hopeless. This is the opinion of Richard Moreno, member of the Chocó Interethnic Solidarity Forum (Fisch), a space in which black and indigenous communities are promoting a humanitarian agreement for that region, which suffers constant forced displacements and confinements due to the confrontations between the AGC, the ELN and the Public Forces.

"The signing of the Agreement generated some levels of tranquility that we had not had, but it lasted about one or two years. We believe that the national government intentionally did not exercised control, with social investment, the territories left by the FARC and allowed the recycling and reconfiguration of armed actors, the same ones that were already there and others that have arrived. Today we continue with the same absence and denial of the State, the same apathy of the local governments and the communities continue to suffer the worst consequences.

And the authorities?

In the midst of the current spiral of violence, in which year after year the murders of social leaders and former FARC combatants in the process of reincorporation, massacres, forced displacements and confinements increase, the Ministry of Defense reports figures with which it refutes the criticisms made by different social sectors.

In response to a query from VerdadAbierta.com, that government portfolio asserts that in order to consolidate and protect the regions where the former FARC were, the National Police carried out 866 operations between November 24th, 2016 and last September 30th, and the Military Forces maintain eleven joint "major operations" throughout the country.

Furthermore, that, in order to comply with the objectives of the Defense and Security Policy, it has executed the Strategic Plan Stabilization and Consolidation Victoria, the War Plan Victoria Plus and the current War Plan Bicentennial Heroes of Freedom.

It also presents achievements in terms of drug seizures, destruction of narcotics processing laboratories, eradication of hectares cultivated with coca and captures related to illegal mining, which are the two main sources of financing for criminal groups.

On the other hand, it highlights that the operations of the Public Forces allowed the capture, killing and demobilization of 27,281 members of the ELN, the 'Clan del Golfo' (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia), 'Los Caparros', 'Los Pelusos' and 'Los Puntilleros', among other illegal armed groups. It also reports that, in the last five years, 358 uniformed members of the Armed Forces and the National Police were wounded and 98 were killed.

If the state security forces have acted consistently in the so-called post-conflict period, as these figures reveal, why is violence soaring in some regions?

Andrés Cajiao, of FIP, states that the role of the security forces has been differentiated and has had different effects. According to his analysis, it has managed to prevent the strengthening of some FARC dissidents, as in the south of Tolima, but its actions have also generated criminal disorder: "By attacking major leaders, the groups fragment and new scenarios of violence are generated”.

And he adds: "In general, the state has been reactive. It puts out large fires when violence and homicides rise drastically, deploying more force. The security forces have been slow to adapt to the new logic of confrontation, where there are no longer direct confrontations and the groups try to be less visible”.

Currently the armed groups have a greater capacity for redrawing, Cajiao maintains, and asserts that "they are no longer those supremely hierarchical structures, in which eliminating a leader implies a strong structural change or a difficult to replacement. They are increasingly more dynamic and horizontal”.

Jorge Restrepo, professor at the Javeriana University and director of the Conflict Analysis Resource Center (Cerac), considers that the Peace Agreement alone is not enough to respond to the current security problems. For this reason, he argues that it is necessary to reform the security sector for the post-conflict period, as well as the justice system, which lacks measures to deal with organized crime.

"Why are we living in violent times despite the peace process," asks Restrepo. And he answers: "Because the end of the conflict with the FARC was only convenient for the organized crime groups. In that ending of the conflict, the absence of policies against organized crime ended up helping it to reinvent itself and expand. This reorganization process ended up being particularly violent".

The integral application of the Peace Agreement is a demand of different social sectors. They believe that if the Comprehensive Rural Reform, the Comprehensive National Crop Substitution Program (PNIS), the National Commission for Security Guarantees, among other measures, were to advance at the right pace, the outlook would be different.

"Each point that has not been implemented or has been implemented drop by drop has facilitated the recycling of violence. The Peace Treaty cannot be applied little by little because it is comprehensive. Point 3.4, which has to do with security guarantees, has failed because more than 290 ex-combatants have been murdered, but it could also be said that the PNIS was not applied in the first six months and it was key to take power away from the mafias," says Gonzalez, from Indepaz.

At the end of the day, as it happened in the hardest period of the armed conflict, those who bear the consequences are the inhabitants of the countryside, the indigenous reservations and the community councils of the black communities. Once again, they are at the mercy of those who settle on their lands with weapons slung over their shoulders or holstered in their pants.

"The peace process was a failure for those of us who suffered the armed conflict. It did not allow the vision and desires that the communities had: to no longer hear gunshots, to live peacefully with their families and to have peaceful nights dreams. Today that tranquility is not reflected. Parents mourn the recruitment of their children and suffer threats for wanting to rescue them from the armed groups", reproaches with great emotion the indigenous leader Juan Manuel Camayo from the Cauca mountains, where the roaring of the rifles don’t stop.

That was the case and still is for different regions of Colombia, where five years after of the promise of the non-repetition of the violence was confined in the 310 pages of the Final Agreement for the End of the Conflict and the Construction of a Lasting and Stable Peace.