“At breakfast one can guess what lunch would be,” goes the saying. This phrase exemplifies the implementation of the set of safeguards that the native peoples were able to include, at the last minute, in the pact that put an end to more than 50 years of confrontation between the Colombian State and the once oldest guerrilla group in the continent.

Breakfast comes to be the peace dialogues that the government of then President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) and the extinct FARC guerrilla held in Havana, Cuba, between November 2012 and August 2016. Since it was announced that a negotiating table would be established to discuss a six-point agenda to build a stable and lasting peace, Afro and indigenous people asked to be allowed to participate.

Despite their insistence, their words were not heard, as was the case with the Gender Sub-Commission, which was created to guarantee the rights of women and members of the LGBTI community to be harmoniously included in the Peace Agreement. In the face of the refusals, ethnic communities responded with more insistence and various advocacy actions, such as the creation of the Ethnic Peace Commission to join efforts and even ask for support abroad, especially before the U.S. Congress.

Not giving up finally paid off: between June 26 and 27, 2016, the negotiators of the national government and the extinct FARC received a delegation of ten representatives of the black communities, ten from the indigenous communities and two from the Rrom communities.

By that time in Cuba, five of the six points of the future Peace Agreement had already been agreed upon. The ethnic delegates had little room for maneuver and they had to return to the Caribbean Island in August. For that reason, of the 310 pages that make up the peace treaty with the FARC, only four give life to the Ethnic Chapter.

On the 24th of that month, when it was announced to the world that “everything was agreed”, the Afro and indigenous representatives were still fighting for their rights. They finally succeeded in having them enshrined as Point 6.2 of the Final Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace.

Its guiding principle recognizes that ethnic communities “have suffered historical conditions of injustice, as a result of colonialism, enslavement, exclusion and having been dispossessed of their lands, territories and resources; they have also been seriously affected by the armed conflict”.

Feliciano Valencia, an indigenous member of the Nasa people and senator of the Republic for the Indigenous and Social Alliance Movement (MAIS), explains that the Ethnic Chapter contemplates four safeguards that prevent the implementation of the Havana agreements from being detrimental to the rights of ethnic peoples. For this reason, any so-called post-conflict policy must preserve the primary and not subsidiary nature of free and informed prior consultation; the right to cultural objection as a guarantee of non-repetition; the cross-cutting ethnic, gender, women, family and generational approach; and the guarantee of non-regression.

Such was the ‘breakfast’ of the Ethnic Chapter and for the last five years its ‘lunch’ has been served. And as the old saying suggests, its implementation is being similar to its negotiation, as it has been full of delays, non-compliances and refusals.

New scenario, old habits

Just as the ethnic communities were heard only at the end of the peace dialogues, the same happened with the construction of the Implementation Framework Plan (PMI), which is the roadmap for translating the provisions of the Peace Agreement into public policies.

“Four months were available for the implementation of Point 6.1, related to the development of the Implementation Framework Plan. The government immediately continued with the parameter of systematic exclusion of ethnic peoples: we did not begin the construction process, even though the safeguards of the Ethnic Chapter established it,” explains Helmer Quiñones, coordinator of the advisory team of the Special High-Level Instance with Ethnic Peoples (IEANPE).

To rectify this shortcoming, the communities resorted to their most powerful tool: protest. “We ended up participating also at the end of the Implementation Framework Plan, between the months of September and December 2017, but as a product of the indigenous and Afro-descendant minga that blocked the Pan-American Highway and forced the government to make us participate in the process,” recalls Quiñones.

Only by the de facto ways, the four pages of the Ethnic Chapter became 80 provisions and 97 indicators, distributed in 27 pillars in the six points of the Peace Agreement. This delay has been constant in the implementation.

According to the most recent report of the Kroc Institute of the University of Notre Dame, which monitors the level of implementation of post-conflict policies, until last June, most of the ethnic points were below minimums.

As a result of this pachydermia, Richard Moreno, coordinator of the Afro-Colombian Peace Council (Conpa) and member of the Chocó Interethnic Solidarity Forum (Fisch), affirms that ethnic peoples have a bittersweet feeling about the Peace Agreement.

“We had high hopes and aspired that the Ethnic Chapter would serve to advance in the backwardness that, historically, our communities have had, in terms of unsatisfied basic needs. In our overall assessment, implementation is around eight percent. And the advances are not precisely in the most transcendental points that we need,” he laments.

Charo Mina, a member of the Black Communities Process (PCN), which brings together dozens of Afro-Descendant organizations, agrees with Moreno, detailing that the few advances have been in small infrastructure projects.

“That is very problematic because it means that it is not related to the priorities established by the Ethnic Chapter, at the level of territorial rights, but is more related to the commitments of the national government with the territorial entities, which are not our priorities as ethnic peoples. There is no titling or expansion of collective territories, nor return opportunities for the displaced,” Mina points out.

Land, the main debt

Different Afro-descendant and indigenous organizations agree that there are huge failures in the Integral Rural Reform. They even point out that the national government is inflating the number of hectares awarded through the nascent Land Fund.

Camilo Niño, president of the Technical Secretariat of the National Commission of Indigenous Territories (CNTI), tells that they found out about this situation when the National Land Agency (ANT), notified them that they had been awarded 245 thousand hectares from the Land Fund, product of the implementation of the Peace Agreement.

“Upon review, we found that the 245 thousand hectares come from processes that were underway before the peace agreements were signed. For example, we have a reservation that had requested its extension 42 years ago and others that corresponded to judicial processes, but were included as a result of the Peace Agreement,” he explains.

Niño emphatically states that such granting is not possible because the requirements defined for that purpose have not been met. “A FISO (Registration Form for Management Subjects) and an indigenous RESO (Registry of Management Subjects) had to be constructed that would be differentiated from the peasant one. To date, there is no ethnic FISO, nor an ethnic sub-account in the Land Fund. That is why we are still wondering where these lands came from, if the differential instructions that the decree law considers do not exist”, he argues.

In this regard, Mina, of the PCN, asks that the safeguard that established that the claim processes that the ethnic communities had been carrying out before the signing of the Peace Agreement would not be included as part of the implementation be respected.

“The government has shown collective titling that does not correspond to the commitments of the Agreement, but to commitments that came from the past. This means that the new commitments are not being fulfilled,” he insists.

About the debts that they hope the Peace Accord will help to settle, there is a need of around one million hectares for 200 community councils that are requesting collective titling. “There are community councils that have lost spaces and have never achieved their collective titling, such as the 40 in northern Cauca, because different governments have refused to recognize that there is an Afro-descendant community in those territories”, refers Mina.

In a similar situation are 779 indigenous reserves throughout the country, which have been acquiring land by their own means through the General System of Participation, but which have not been annexed to their collective titles. In the offices of the ANT there are 1,014 requests for expansion, constitution and regulation.

On this particular point, Niño, of the CNTI, clarifies that it is not true that the indigenous peoples are demanding that the State buy and adjudicate them millions of hectares, because “we already have use and possession of many areas that only require formalization”. Although he does not rule out that some indigenous reserves do require adjudication.

And the Guards?

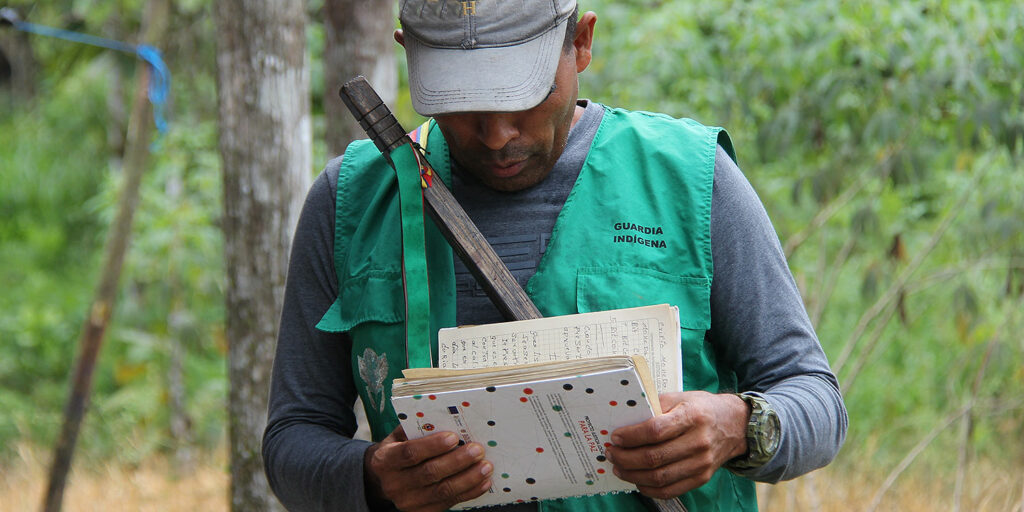

One of the few mentions with its own name in the four pages of the Ethnic Chapter is dedicated to the collective protection mechanisms of the native peoples. “The strengthening of the ethnic peoples’ own security systems, both recognized nationally and internationally as the Indigenous Guard and the Maroon Guard, will be guaranteed,” it requires.

Armando Valbuena, secretary of the IEANPE, an entity created by the Peace Agreement to follow up on the implementation of the ethnic provisions, states that it is still a debt due to the lack of political will of the national government and that they have been given few resources.

“The National Protection Unit has supported with resources some of the main processes of collective protection, but they are not a state policy for territorial control to be exercised. In the Pacific we are present in 30 municipalities and we do not have the necessary resources for the mobilization of the guards. We need simple things like communications in regions without connectivity, that is why we ask for communication radios and it is a long process that has not been accepted”, he says.

The situation of the Maroon Guard is worse because it has no legal recognition. “There is a discrepancy with the national government to recognize this Guard as a mechanism that is part of the government system of the black people and it has been very difficult to reach an agreement,” says Mina.

And he continues: “There is a discriminatory act on the part of the national government with respect to the Maroon Guard. It does not need a law to be recognized, it has the recognition for being part of the struggle process. This is within the framework of discriminatory actions of the government. There is no political will to recognize the Afro-descendant people”.

Edwin Mauricio Capaz, one of the spokespersons of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (Cric), says that the Guard in that region has received some logistic equipment that is not sufficient for the contexts of violence it faces: “They have given boots, radios, vests. Useful things for daily use, we are not going to undervalue what has been given; but boots and vests every year, compared to what we assume, is not enough for the adverse dynamics that exist in our territories, which merit greater efforts. Surely they would be enough in other contexts”. Between 2016 and 2020, only in the northern part of Cauca, 175 indigenous community members were killed.

Integral System, a different story

In the implementation of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the Truth Clarification Commission (CVE) and the Unit for the Search for Disappeared Persons (UBPD), unlike other measures of the Peace Agreement, ethnic communities were taken into account. These three entities give life to the Integral System of Truth, Justice, Reparation and Non-Repetition.

In this regard, Helmer Quiñones, from IEANPE, states that this case shows how the correct implementation of the safeguards of the Ethnic Chapter changes the destiny of the native peoples.

“The selection mechanism received the message that it had to implement an ethnic and racial approach. That is why care was taken in choosing Patricia Tobón and Ángela Salazar to the Commission; we had the possibility that eight of the 38 magistrates are ethnic; and in the Search Unit we had an equal referent and with its director we designed a more sophisticated consultation mechanism and we have paths of dialogue that allowed the National Search Plan to have specific chapters for Afros and indigenous people”, he refers.

For Marino Córdoba, president of the Association of Displaced Afro-Colombians (Afrodes), despite the fact that the Integral System has been strongly opposed by the national government, it is the only component that so far is yielding concrete results for ethnic communities.

“It hurts to hear that reality, but for us it is important to understand how the conflict affected us in a differential way. There has also been progress in terms of participation, in the construction of reports, in presenting our points of view, we have been heard and we are represented. The only thing we can highlight from this whole peace process, with limitations included, is the Integral System”, he specifies.

Regarding the indigenous communities, Senator Valencia points out that the work of the three entities created to repair the victims of the armed conflict can generate “a recognition and a truth about the conflict from the voices of the indigenous communities themselves, because although the armed conflict has deeply affected many social sectors and rural communities, the impacts it has had on the indigenous communities have a particular meaning since they transcend individuality and have permeated the collective subject”.

The magnifying glass of the control entities

The Attorney General’s Office and the Comptroller General’s Office have closely monitored the implementation of the Ethnic Chapter. In different reports they have questioned the delay in its implementation and asked for speed in settling the debts with the ethnic peoples.

In its Third Report to Congress on the State of Progress of the Implementation of the Peace Agreement, presented last August, the Public Prosecutor’s Office concluded that the application of the Ethnic Chapter, five years after the signing of the Peace Agreement, is at a very low level.

“The peoples continue to suffer the historical conditions of injustice and inequity and continue to be seriously affected by the dynamics of the reconfiguration of the internal armed conflict and the intensification of violence in the territories,” it states.

One of his main criticisms was directed towards the management of the Land Fund, since the ethnic sub-account is not yet regulated and has no funds allocated. And in line with the denunciations made by CNTI and PCN spokespersons, he points out that the constitution of three indigenous reserves and the expansion of two others are not related to the Peace Agreement, as reported by the ANT.

In this regard, Emilio Archila, senior presidential advisor for Stabilization and Consolidation, explains that the goals achieved during the government of President Iván Duque (2018-2022) are more than satisfactory, as they have managed to enter the land bank 1.2 million hectares in the last three years, when the goal for 15 years is three million, and of the 7 million hectares that were projected to be delivered to peasants without land or with very little, more than one million have already been granted.

“There is both a political and legal discussion that has to do with land formalization. In the reading made by the Attorney General’s Office, the lands that come from previous processes should not be able to be counted and neither should those that are uncultivated, but our vision is that we need peasants with land”, emphasizes the official.

The lags of the Integral National Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS) were also highlighted because it does not have an ethnic approach and only until December last year, a consultation with the indigenous communities was agreed for its execution, but the national government “expressed its will to implement the program in territories that have not been formalized as reservations, so there would be no consultation with the communities that inhabit these spaces”.

Another point pointed out by the Attorney General’s Office is that the prior, free and informed consultation “has not been effectively carried out in the communities, so there is a high risk of regression in this aspect”. And it also questions the fact that only until March of last year, a budget allocation was made to the IEANPE so that it could fulfill its mandate to act as consultant, representative and interlocutor on issues related to the Ethnic Chapter.

On their behalf, the main criticism of the Comptroller’s Office is that five years after the signing of the Peace Agreement, there is no indicator to measure the budgetary investment to comply with the implementation of the Ethnic Chapter.

In its radiography, the fiscal entity agrees on several points with the Procurator General’s Office. But it presents hard findings on the land issue, the most sensitive for the ethnic communities due to their needs and cosmogony. It established that, up to March 31 of this year, none of the National Plans for Integral Rural Reform had effectively incorporated the ethnic approach.

“The participation of ethnic peoples in the design and implementation of the National Plans has not been guaranteed, since in addition to the lack of a strategy for the attention of this communities, in some cases (water, irrigation) the absence of an ethnic differential approach has been justified in the universal nature of the public service, and although in the remaining cases it is mentioned in the text of the Plan, it is only pointed out as a differentiating criterion”, he detailed.

All these debts, in addition to the resurgence of violence in the reservations and community councils, by new and old armed groups that dispute the territories controlled by the former FARC, show that the Ethnic Chapter is confined to the four pages of the Peace Agreement.

Nevertheless, the Afro and indigenous communities have asked their leaders to continue fighting for the implementation of the Ethnic Chapter, because they do not lose hope of living in peace.